The story of Pacifica Radio is a cyclical saga of factional warfare, class and racial struggle, and the power of the self-preservation instinct. “People talk about their tenure at these stations as if they’d just returned from a war zone,” says a long-time producer, who has spent 40 years watching Pacifica’s dysfunction blossom and gradually destroy the network. Pacifica’s public image as a bastion of progressivism — a “voice for the voiceless” — hides from the public the cutthroat rivalries and perpetual infighting that have made the station a notoriously dysfunctional swamp. Long-time broadcasters call it the “end of the line” for radio — its stations rank dead last in their markets in New York, Los Angeles, Berkeley, Houston, and Washington DC — but hope springs eternal, and every so often a visionary programmer revives the seemingly doomed network. The last Golden Age of Pacifica ended almost twenty years ago, however, and it’s doubtful that the network can be saved.

Democracy Now! launched in 1996 on Pacifica as its flagship news show, offering current events, analysis and opinion with a focus on stories ignored or underreported by the mainstream news establishment. It was the network’s only money-making program, annually earning $500,000 in syndication fees from more than 100 stations outside the Pacifica network and $250,000 from archival purchases. Democracy Now was founded by the network’s Program Director, Samori Marksman, and initially featured a rotating crew of hosts from each of the five Pacifica stations, a structure that was only later eclipsed by all-Amy Goodman, all the time. It was a shining example of collaboration, of how an excellent program arises from skilled individuals working together to achieve a goal. Particularly in the midst of the legendarily dysfunctional Pacifica network, which veteran news producer Paul DeRienzo calls “the elephant graveyard of radio,” Democracy Now was a diamond in the rough. Marksman was a well-liked figure at the network, capable of cutting through the petty rivalries and inspiring staff to create quality programming. Back then, according to DeRienzo, people might argue ferociously, but they’d go out for coffee afterwards.

“Legendarily dysfunctional” is an understatement in the eyes of many who labored in the trenches of Pacifica from the 1970s on. Network management has a lengthy track record of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, according to veteran programmers. One likened going to work there to “intentionally climbing into a sewer every day with no boots and no hazmat outfit,” describing a “full-on hate campaign” unleashed in response to the brightening fortunes of WBAI, Pacifica’s New York station, during the mid-1970s. Fund drives fueled by a new audience and a shift toward more positive programming began to put the station reliably in the black, allowing them to pay bills and even salaries. But the old guard was apparently threatened by the arrival of new, empowering programming and the growth of an audience that was receptive to this material. As one WBAI lifer told him, “Anyone successful and happy they’re going to hate. These people live in emotional poverty.” The station became ground zero for intense factional warfare — on one side, people whose identities were tied up in the WBAI of the 1960s, who had offices and 24/7 access to the building but often no show or even official broadcasting duties. On the other hand, there were the new voices like the programmer, a best-selling author whose massive audience followed him to the station and who believes his success made him the lightning rod for these individuals’ anger. His producer was reportedly driven away from the office by an escalating terror campaign of misogynistic comments, air tapes cut with razor blades, and finally human feces inserted into her mail. The newcomer’s attempts to find common ground with his alleged tormentors — sharing stories of his working-class beginnings, arriving in New York on a Greyhound bus, or his work with over a dozen activist movements that effected real social change during the 1960s and 1970s — were rebuffed. “This isn’t a good mix,” he was told; “Why don’t you just go back?” The station remained a battleground even as its new direction attracted more positive hosts and intelligent voices than any other time in its history. By the 1990s, Pacifica seemed to be at the top of its broadcast game. At the same time, veteran programmers and management attested to the seething undercurrent of resentment, of racial, class, and ideological hatreds, fomented by WBAI lifers who would rather see the station die than compromise their politics.

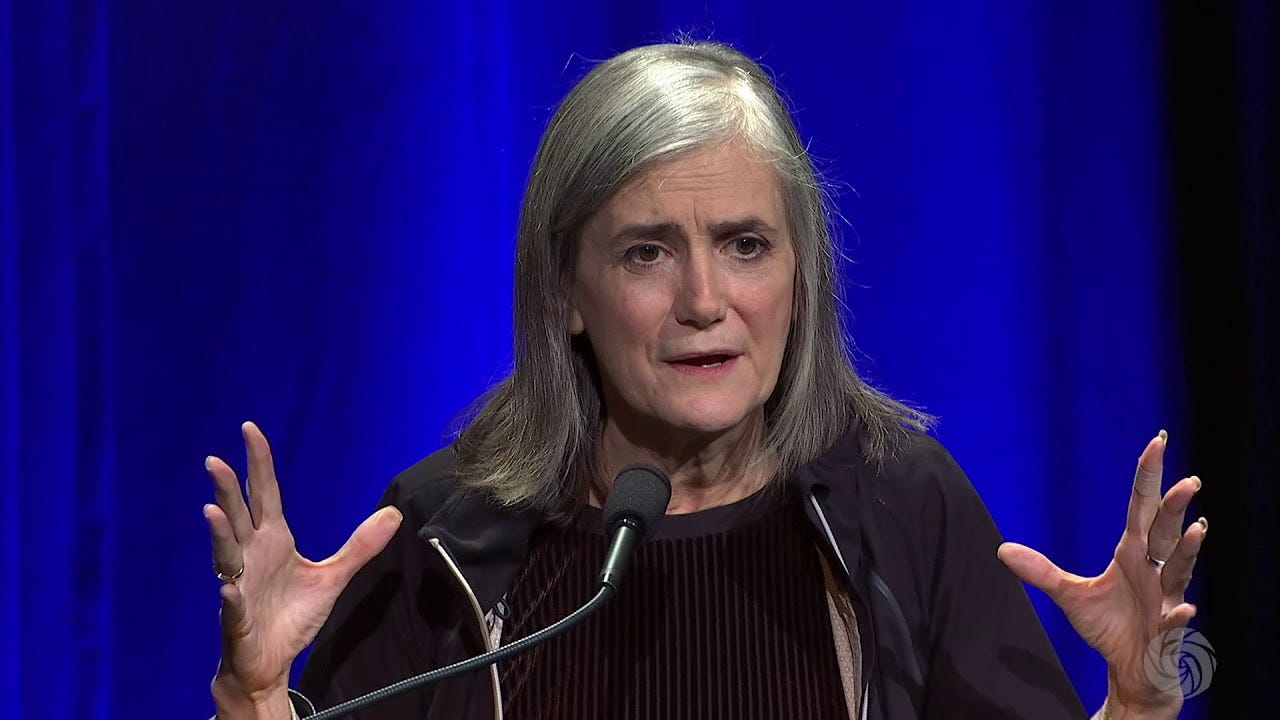

Enter Amy

Amy Goodman arrived at WBAI as an entry-level reporter, her way paved by a long-term charitable donation bestowed by her grandfather as a reward for allowing Goodman opportunities above and beyond a typical internship. The money opened doors in the news department, freeing her to pursue whatever stories she liked without being told what to do by senior staff or having restrictions placed on her use of Pacifica resources. While she demonstrated intense dedication to her craft, colleagues say she lacked any of the social niceties required to work in a newsroom (“Amy doesn’t talk, she yells,” goes a recurring complaint), and the “adults in the room” — Marksman and General Manager Valerie van Isler — generally gave her what she wanted in order to keep the peace. What she wanted, former co-workers say, was full control of her immediate environment, access to Marksman’s treasure trove of progressive contacts, and free use of all resources (finances, equipment, even interns) she claimed to require to do her work. If anyone complained or objected, she reportedly threatened to halt her grandfather’s largesse, eventually terrorizing the anemic and understaffed news department into making her News Director of WBAI.

According to DeRienzo, Goodman landed at WBAI only after being kicked out of WNYC, where the behaviors that made her notorious at Pacifica were not tolerated. NPR’s professional standards apparently left no room for Goodman’s histrionics, her high-volume temper tantrums, and her violent reactions to criticism. These behaviors were merely quirky at WBAI, which over the years had become a collection basin for the detritus of New York radio — people who might be talented but who could not handle the stress of producing radio in the big city and who had, in DeRienzo’s words, “snapped.” There was a sizable contingent of “troublesome” personalities who had, for whatever reason, reached the end of the line — a “brotherhood and sisterhood of losers who would make sure that any attempt at change would be nipped in the bud.” Goodman endeared herself to these people, who were looking for a champion, a “celebrity” who could serve as the presentable public face of the radical Left. She had already amassed a hefty support base among college students and enjoyed a close relationship with big Harvard names Noam Chomsky and Ralph Nader, but she reportedly understood the importance of having the “losers” on her side as well. The word “Machiavellian” inevitably surfaces when discussing Goodman, especially with people who knew her at the beginning of her career.

Some considered Van Isler to be an ineffective General Manager, with lax professional standards and an “anything-goes” attitude in keeping with the station’s reputation as a home for radio rejects. Goodman was one of many WBAI staff to sign a petition to replace her. Her apparent disregard for van Isler not only did not foster animosity from the General Manager, but perversely drove van Isler closer to Goodman, which onlookers have analyzed as van Isler seeking to ingratiate herself with power in order to be spared the axe. A former senior WBAI producer says Goodman took full credit for projects undertaken as collective WBAI efforts and happily sucked up every spare dime at the cash-strapped station. Unlike the station’s own bookkeeper, Sybil Wong, she had the freedom to write checks and sign for at least one bank account, through which she allegedly channeled donations meant for WBAI and Pacifica projects into her own. Van Isler colluded in the charade, reportedly representing to foundations and donors that their money was going to Pacifica and WBAI even as it piled up in the coffers of a parallel organization run by Goodman. An anonymous report disseminated by Pacifica Board member Steve Brown claims the Goodman account’s existence was never revealed to Pacifica — that there is not even an official record of its existence, and that for this reason Wong was not allowed access to the books she was supposed to keep, preventing her from doing her job effectively. Former General Manager Utrice Leid concurs, claiming “absolute criminal activity” by Goodman involving secret accounts and the redirection of funds with Van Isler’s cooperation. DeRienzo recalls fundraisers where large sums of money were raised for Pacifica and disappeared into Goodman’s secret accounts in New York and California, never to be seen again. Concerned about the size of the donations that he claims were vanishing, he consulted with a private investigator, who laughed and explained that a non-profit designation was essentially a “license to steal.” Another long-time producer, who requested to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation, actually witnessed garbage bags full of cash from a fundraiser being turned over to Program Director Bernard White, who crammed them under his bed. Brown confirms that a former assistant of White told him she was responsible for taking trash bags full of fundraiser cash back to White’s apartment, where she counted the money and stashed the bags under the bed.

Mutiny Takes Shape

Reportedly not content to run Democracy Now within the confines of Pacifica, Goodman was busily building up a parallel structure within WBAI, assisted by all the station equipment and funding she could lay her hands on, according to Leid. She constructed a powerful support base using Marksman’s connections and threw herself into accumulating power, positioning herself in Leid’s words as the “sole progressive voice” on New York radio. Former station staff say she befriended wealthy liberal donors and fostered a cult of personality alien to the ethos of other WBAI hosts, who preferred to give credit to the network and work within the collective. DeRienzo confirms that Goodman became the Genuine Leftist Celebrity to whom Democratic real estate investors, Hollywood millionaires, and other big-name liberals could point as a recognizable face they were proud to support; a role model for the crowds of college students who attended her speaking engagements on their campuses and a champion for the listeners who loved her and knew or cared nothing about the complaints of her co-workers. Leid calls her a “George Soros capitalist” — a ruthless, by-any-means-necessary, screw-the-consequences pursuer of what’s best for Amy Goodman.

Marksman died in March 1999 and was replaced by White, who had no management background, having worked as a station DJ prior to his promotion to Program Director. With the inexperienced White at the helm, Goodman was free to take the gloves off regarding her “ownership” of Democracy Now. When Steve Yasko, National Program Director, attempted to reform the program along its original lines, with a rotating crew of hosts from each Pacifica station, Goodman reportedly initiated a scorched-earth campaign against him with fake “confidential” memos that created the impression of a targeted harassment campaign against Goodman. The implication was that Pacifica was, cruelly and without cause, trying to take away “her” program. Yasko was depicted as a misogynistic porno merchant with such effectiveness that he not only received threatening calls from listeners who had bought Goodman’s lies, but saw them show up both at WPFW headquarters and at his residence. According to one former producer, Goodman also attempted to bankrupt Pacifica with a passel of frivolous lawsuits alleging “harassment, civil rights violations, a hostile work environment, and other despicable lies.” These she spun as Pacifica suing her, ever the victim, even as she allegedly alienated her AFTRA union lawyers by forcing them into service in her unjust war. DeRienzo says the union essentially quarantined her into a one-person “shop,” aware of her legendary inability to work well with others. When the AFTRA lawyers finally refused to take part in her crusade, she reportedly fell back on a network of wealthy and well-connected lawyer friends — the same lawyers who would later write the contract that handed her ownership of Democracy Now.

Having pried control of Democracy Now from the admittedly weak grasp of Pacifica management, Goodman proceeded to milk it for all it was worth, producers say. She allegedly demanded that every Pacifica station carry the program during morning and afternoon drive times in addition to the Goodman-hosted evening news hour (and demanded a separate salary from each program!). She was to receive an additional “discretionary” budget for Democracy Now, which while it would come from Pacifica’s coffers would not be controlled by Pacifica or any of its program directors, including Yasko. She got office space in DC and New York, with equipment, including the station’s equipment when needed, and staff to run it. Even when not physically present, she cast a long shadow over the office — “her people” enjoyed priority use of the best equipment, and woe betide any producer who defied her, according to DeRienzo, whom she allegedly screamed at over the phone when he sat down at the “good” tape machine an intern of hers coveted.

Around this time, Van Isler was let go, having been effectively overwhelmed by the stressful station environment, according to one veteran producer. She was not fired outright, but instead offered a higher-paying position in Washington DC. Only after repeatedly declining this post was she dismissed. The Pacifica Campaign, a “listener movement” against the National Board led by Goodman’s Democracy Now co-host, pointed to her dismissal as indisputable evidence of a “purge,” which mushroomed into a “coup,” that signaled the growing influence of shadowy corporate interests intent on selling out Pacifica to the highest bidder for personal gain. The Campaign called for listeners to respond by boycotting pledge drives, boycotting the station, calling management, and picketing station offices. This outpouring of support seems disingenuous given that Goodman and the other Campaign ringleaders at WBAI had actually signed the petition calling for van Isler’s dismissal. When Pacifica Executive Director Bessie Wash tried to promote News Director Jose Santiago to replace Van Isler, the Campaign blamed him for her departure and allegedly began a targeted harassment campaign that — in combination with a major family health crisis — forced Santiago to turn down the post. While the Campaign claimed to resent Wash’s imposition of her choice of manager upon the station, citing the appointment as a classic example of the National Board’s dictatorial rule, the Pacifica Foundation’s bylaws had already been ignored once when van Isler skipped over Utrice Leid — the WBAI staffing committee’s first choice to replace Marksman as Program Director — and runner-up Laura Flanders to select White, who received zero committee votes. Van Isler, defending the choice of her personal friend over the committee’s preferences, claimed the selection process was “tainted.” Invoking the bylaws after that flagrant breach of procedure was closing the barn doors after the last horse had long since galloped away.

Wash finally convinced Utrice Leid to take the post, on the condition that there would be no firings, no bannings, and no interference from the National Board. In December 2000, Leid joined as interim General Manager, making it clear she did not want the job on a permanent basis but was merely there to help right the ship. The Pacifica Campaign was worried, according to producers then at WBAI, as the professionalism Leid mandated was several notches above Van Isler’s anything-goes attitude. The same day Leid joined, Wash fired White for “using his forum to criticize the board unfairly.” There was an air of impropriety about the proceedings only because van Isler had slighted Leid to promote White, and the Pacifica Campaign exploited this fact to spin White’s firing as an unprofessional and vindictive act.

Leid soon came in for criticism for taking people off the air unilaterally, without recourse to union mediation or open discussion, according to contemporary reports. She backed Wash in firing White without consulting the union, an act which cemented the Pacifica Campaign’s loathing and opposition to her. Leid’s common-sense edict of “don’t defecate on the airwaves” didn’t sit well with the malcontents accustomed to airing their dirty laundry publicly. She removed Ken Nash for personally attacking her on air, silencing him in the middle of his show (not long after removing his co-host, Mimi Rosenberg). Some staff complained that her supporters had free reign to attack those who had been banned or fired, whatever their crimes, while their victims had no recourse or opportunity to address the criticism on air. Leid was also criticized for replacing hostile personalities with friends and cronies. However, she did bring a sense of order and professionalism to WBAI, which sorely needed her discipline, and was praised for keeping the station on air in the aftermath of 9/11 — even while she herself was subject to intensifying personal attacks. Rosenberg and White reportedly drove through her neighborhood, screaming abuse at her as she walked home. Her house was repeatedly broken into, and libelous flyers were distributed throughout her neighborhood. Despite her standing in the community — she founded and ran the City Sun, a popular newspaper written by and for New York’s black community — neighbors began to shun her, believing that where there was smoke, there must be fire.

The “Plot” Thickens

The Pacifica Campaign sought allies not only among listeners but within station staff, claiming the Board was controlled by corporate interests looking to sell the network’s stations. Goodman’s Democracy Now sidekick resigned from the program in January 2001 to run the Campaign¹, which allegedly resorted to smearing individual Board members while promoting rumors about the impending corporate coup. Pacifica’s Board was said to be plotting to sell off WBAI and KPFA’s commercial licenses, worth hundreds of millions of dollars, so that they could share the profits among themselves. Evidence to support these claims was debatable, but the group cobbled together a convincing propaganda campaign out of a few scraps and repeated the threat until listeners began to believe, assisted by the trust that listeners tend to place in their favorite radio personalities. The “losers” Goodman had befriended early on, many of whom had been fired as Leid tried to impose some semblance of professionalism on the station, were promised their shows back and more — anything to get them on board the war effort, according to DeRienzo.

According to a veteran producer, the corporate-takeover rumors stemmed from a yearly meeting of the Pacifica Board during which time they shared their wishlists for network changes in the coming year. The treasurer calculated the cost of the desired changes, which generally ran to millions of dollars, far outside the means of the perpetually-struggling Pacifica. Board members then brainstormed how they might raise that money, and one member — usually a different person every year — would suggest selling off a commercial license to raise funds — either to buy a new station, to invest the proceeds in the other four stations, or as a license-swap exchanging the valuable commercial license for a noncommercial license. Board members could not legally profit at a personal level from such a sale, which at any rate remained in the realm of the hypothetical. It was not a plan of action, and none of the dissident Pacifica Campaign members could provide proof such a plan existed. Still, they strung rumors about the national meeting together with an undated memo from Micheal Palmer discussing the sale of WBAI and KPFA, which they claimed was contemporary but which one producer stated dates from 1966. The email, if indeed it is an email, contains multiple red flags that could cast doubt on its legitimacy — questions concerning how it landed in the inbox of a Pacifica Campaign supporter instead of its intended addressee, for instance² — but it was published in FAIR, CounterPunch, and other outlets to great effect. The “impending corporate takeover of Pacifica” scare was enough of a story to fool the listeners who worshiped Goodman and wanted to believe she was David rather than Goliath in the battle for Pacifica.

The rest of the Pacifica Campaign’s “issues” concerned local stations’ perceived lack of influence on the national level. A coalition of Pacifica listeners was granted legal standing to sue for the “public benefit,” alleging that the Pacifica National Board was acting unilaterally without consulting local station boards or those stations’ listeners. National management, the suit alleged, was centralizing power in preparation for the dreaded sell-off, appointing cooperative personnel to manage the local stations. A second lawsuit was filed by Dan Siegel (who later joined the same National Board he had sued as both Executive Director and General Counsel) on behalf of the local station boards. Goodman herself sued Pacifica for “defamation” after she was reprimanded by the National Board for allegedly using the network’s press credentials to sneak Ralph Nader onto the floor of the 2000 Republican National Convention, where she interviewed him. The defamation suit followed closely on the heels of a Pacifica financial statement showing Democracy Now had made nearly $300,000 for the network; given the Pacifica Campaign’s apparent philosophy of “the ends justify the means” — the campaign leader compared their struggle to that of communist revolutionaries like the Bolsheviks and Sandinistas — some have speculated that Goodman’s suit was an attempt to stake her claim to that cash.³

Because Goodman’s clique was so focused on seizing power, and willing to pursue what many witnesses deemed underhanded smear tactics in order to secure the network for Goodman, they had a natural advantage over their enemies, who were focused on their jobs: creating community-focused, responsible radio programming. Looking back at the conflict, Leid recalls her certainty that Pacifica would be sorely needed in the coming years, with the convergence of “strange political forces” heightening the sense of urgency she and her allies felt. But the voices pleading for civility and a focus on Pacifica’s mission were lost in the maelstrom, while the Goodman faction reportedly weaponized listeners by leveraging the trust they placed in their beloved radio personalities. According to one producer, the Pacifica Campaign had individual talking points drawn up to justify the dismissal of every enemy figure — dozens of managers and board members were smeared and targeted on- and off-air. KPFK news producer Marc Cooper had opposed Yasko’s hire as National Program Manager but was horrified by what he saw as the Pacifica Campaign’s demonization of Yasko as a slimy porn kingpin (for the crime of letting his web registration lapse and the site’s subsequent colonization by an unrelated smut peddler).⁴ Goodman added injury to that insult by filing a gender harassment suit, telling her followers that Yasko, a gay man, couldn’t handle “strong heterosexual feminists” like Goodman.

Cooper pointed out that the “issue” targeted by the Pacifica Campaign was constantly shifting, though he failed to take his critique far enough in an article he wrote on the subject — “first the firing of KPFA Manager Sawaya; then it was the Democrats taking over, or was it the corporatists and the commercializers; then, briefly, it was the FBI; soon after, Pacifica’s supposed plan to move out of California; promptly, it morphed into a ‘strike,’ against PNN: and then recently the dastardly ‘Christmas Coup,’ which lasted only until the issue shifted to the National Association of Homebuilders. As I write, the new flavor of the week is Democracy Now!”⁵ Such a bewildering stew of “causes” was reflective of nothing more than the methodical targeting of individual board members, in the opinion of many former staff, some of whom were victimized themselves (Ken Ford was a member of the NAHB, while others were tenuously linked to the other bêtes noires du jour). As the campaign knocked off Board members, it cemented its control over Pacifica — conquest by attrition.

Yasko was finally terrorized out of his position, his physical and mental health severely compromised by Goodman’s attacks. Almost 20 years later, he refuses to discuss the incident. Leid took his place as National Program Director in Washington DC, where she says her arrival was greeted with apprehension by the local staff. More than half a dozen engineers threatened to leave if Goodman even showed up in the building. Leid recalls that she and the national news team produced two news programs a day rivaling Democracy Now in both quality and listener support, leading Goodman to view her as the next big threat to her dominance, and the Pacifica Campaign’s focus shifted to taking out Leid.

Multiple observers confirmed Goodman’s campaign against Leid was heavily racialized despite Goodman being white and Leid black; Goodman had conspicuously surrounded herself with a cadre of black supporters willing to vouch for her “blackness,” an imperative given that Pacifica and WBAI were already staffed with competent and qualified black professionals who had no allegiance to Goodman. Despite roping in marquee names like Harry Belafonte, reportedly with the help of “community outreach” efforts sponsored by her wealthy donor friends, she was unable to block a successful fundraising drive by Leid, and shifted her focus to expanding her power base within WBAI. Her staff proliferated, colonizing the station offices and preventing others from doing their work, even running anti-Pacifica protest campaigns and producing anti-Pacifica content using station equipment while others were trying to produce their shows, according to producers who found it difficult to work in such an environment even as they tried to avoid taking sides in the mushrooming civil war. Some “Amy-bots,” as WBAI staff took to calling them, reportedly moved in, sleeping in the offices overnight, stealing equipment, selling and using drugs, and generally trashing the place. More than one producer claims they caught these new faces rifling through desk drawers and downloading information off hard drives, occupying offices that were not their own.

Because much of station management consisted of highly-educated black professionals, the allegations of racism that periodically surfaced had a surreal aspect. Steve Brown describes the rivalry as between Leid’s “Caribbean black” faction and White’s “uptown black” faction, while some considered White’s primary function to furnish Goodman with credibility in the black community. Particularly given Pacifica’s history of black radicalism, some of the black station staff saw White as an “uncle Tom” figure and resented Goodman throwing her weight around. The matter came to a head when Leid fired White. On the morning show, which he had co-hosted with Goodman, White was replaced by Clayton Riley, a black man who lost no time in criticizing Goodman’s power-grab on air. Listeners and provocateurs called in to defend her, flinging around racial slurs, and the two hosts were soon at each other’s throats. They were kicked off the air and Goodman was relegated to a side studio. According to DeRienzo, she perceived this move as a demotion and summoned her college followers into the station offices through a side door she left unlocked. Dozens of students swarmed in and were only at the last moment prevented from entering the broadcast studio when security guards barred the door.

Van Isler had never secured the station offices with a lock during her tenure as General Manager, violating FCC rules and allowing disreputable elements — one producer called them “street urchins” — to take advantage of WBAI’s hospitality-by-negligence. Rumors grew that Goodman and White, whose offices served as the hub for the protest activity, were planning a full-on takeover of the station, to be parlayed into a takeover of the entire network. Several producers overheard their minions discussing bringing guns to the station, literally plotting an armed coup, and White had openly discussed “taking over” station offices. Word of the impending takeover finally reached Executive Director Bessie Wash, who flew cross-country to help secure the station — to protect both the employees and the station license, which could have been confiscated by the FCC had Pacifica lost control of the premises.

This was the much-maligned “Christmas Coup” — the last-ditch attempt by Pacifica management to save WBAI from Goodman and her followers. Wash merely called in locksmiths to secure the building. Far from “locking out the staff,” they were able to avoid changing the few locks that existed on the premises because staff simply turned over their keys, “colluding” with the “coup plotters” because they did not want to see Goodman’s faction continue abusing the facilities and putting the staff in danger, according to several staff who “survived” the affair. The host broadcasting at the time reported it as if it was a top-secret military operation, and the myth was born, becoming the Pacifica Campaign’s latest cause célèbre. Had Goodman, White, and the rest of their minions succeeded in taking over the station, the FCC could have taken away WBAI’s license, which mandates a station maintain control of its airwaves — hence the need for locks. Far from engineering a coup, her defenders say, Wash was merely restoring order.

Goodman enlisted Village Voice gadfly Nat Hentoff to shore up support for what has been described as her own coup attempt, presenting Leid as a corporate shill and censor-happy fascist and Goodman herself as a champion of truth and justice, having “risked her life to break the story of the slaughtering of independence fighters in East Timor” — a brave act of journalism, to be sure, but even then a decade in the past. Members of the Pacifica Campaign were duly canonized, while National Board members were smeared as agents of Big Business. Ken Ford, the last of the Board to be driven out by the scorched-earth campaign, was introduced as “a manager with the National Association of Home Builders” sandwiched between a professional sports team owner and a commercial real estate broker in an effort to smear by association; in the following paragraph he was called a “high-level player in the corporate world.”⁶ Protesters assembled outside his office, accusing him of squandering the network’s funds and trying to sell off its stations and confusing his coworkers, one of whom called the sideshow “totally irrelevant to the business of the NAHB.”⁷ Protesters thronged parties thrown by affiliates of his employer, handing out leaflets and buttonholing attendees. They posted Ford’s contact information online, so extensively that it’s still there nearly two decades later. They even hounded him on a cruise he took with co-workers, pulling aside the ship in their own boat and holding up massive banners demanding his resignation.⁸ The protests were arranged via dedicated email lists and instructions on how to participate were blasted out to all Pacifica members. Because Goodman, White, and the other ringleaders were popular radio personalities, listeners trusted their version of events and readily turned out to demonstrate against their adversaries, according to Brown, whose own loyalties were influenced by his affinity for Goodman and White’s programs.⁹

Brown was on the front lines of the harassment, being himself responsible for one of the infamous flyers distributed to Leid’s neighbors in an effort to make her a pariah within her community. Though he had never met Leid and knew nothing about her, he believed what Goodman and her cronies said on air and volunteered to participate in the character assassination campaign. Even after meeting Leid at the behest of a long-time friend and station producer, and learning that she was not guilty of any of the crimes his flyer pinned on her (among them that she had bankrupted the City Sun, a newspaper she had actually founded and successfully run for many years and which still exists to this day), he continued to distribute the flyers because she had fired all the people he liked on the air. Brown views his flyer as a small piece of the targeted harassment campaign against Leid by Goodman’s minions, which included multiple break-ins, death threats, and the spreading of malicious rumors among the neighbors in her building, and has in retrospect attempted to justify his participation in the abuse with the rationale that others were doing it too. In the midst of this harassment, Goodman accused Leid of violently assaulting her, spinning the charge out of an incident where Leid restrained Goodman from having what onlookers called a violent temper tantrum. Leid had moved a producer into White’s (empty) office to ease tensions with an on-air host and Goodman, apparently perceiving an incursion on the fired White’s territory, began allegedly shrieking and taking photographs of the producer sitting in White’s office; Leid snatched Goodman’s camera, setting off Goodman’s histrionics (a regular occurrence, according to DeRienzo) and forcing Leid to restrain the flailing Goodman lest she injure herself or others. Goodman finally collapsed, sobbing, and left the building, refusing to return and alleging “hostile workplace violations.”

Wash was subject to the same terror campaign as Yasko, Ford, and Leid. She received bomb threats and death threats credible enough that the FBI advised her to split up her family for their protection. She finally had enough of the Pacifica Campaign’s harassment and announced her departure in November 2001. Leid and several other managers filed out with her in solidarity. Democracy Now was lost, and the combination of lawsuits and loss of revenue from one of the station’s only profitable programs had essentially sucked Pacifica dry, but Leid believes “a hardy band of people across the Pacifica spectrum” ultimately saved the network from Goodman’s clutches. Goodman’s intent, Leid says, was to force Pacifica into bankruptcy in order to swoop in at the last minute to “save” the network with the help of her wealthy donor network. She would have her own personal network of five immensely valuable radio stations, to do with as she (and her well-heeled liberal patrons) wished. Wash, for her part, told the Washington Post she had completed her “five year plan,” leaving the network a better place than she found it, and that even if she was technically fired, her departure was her idea.¹⁰

The vicious harassment campaigns against the National Board and its allies, involving stalking, public harassment, smear campaigns both online and interpersonal, burglaries and break-ins, slander and libel, all occurring systematically, simultaneously, and frequently to the point of physical illness, were the norm for over a year, according to staff on both sides of the conflict. Goodman painted herself as the victim of such harassment on air, riling up her listeners with stories that the evil network was trying to take away “her” program.¹¹ The so-called assault by Leid was only one of many incidents — there were charges of racism, sexism, and the aforementioned “defamation” lawsuit that was her revenge against the Board for criticizing her behavior at the RNC, according to DeRienzo. Listeners, of course, believed Goodman — they had never heard of Utrice Leid, or Steve Yasko, or any of the other villains in Goodman’s radio dramas.

The Spoils of Victory

The Pacifica lawsuits, including Goodman’s, were eventually rolled into a single suit, which was settled in December 2001. The settlement saw the National Board, already depopulated by the scorched-earth Pacifica Campaign, neutered and sidelined. It dissolved the centralization of administrative powers, atomizing the network’s finances such that Pacifica has never really recovered. One hand was legally prohibited from knowing what the other was doing. Pacifica’s newly-“democratized” structure mandated the election of Local Station Boards by listener-members who contributed $25 or volunteered for three hours in a given year. In 2002, the network had approximately one million regular listeners, of which maybe 10% made regular contributions or volunteered. Only 10% of those actually voted in listener elections, making Pacifica listeners perhaps the only “democracy” less enthusiastic about self-government than the United States. The station’s bylaws actually require such a quorum, meaning if enthusiasm slips further, the already dysfunctional institution risks institutional paralysis. Meanwhile, at the time of Goodman’s takeover, only about 300 votes — less than one percent of listeners — were required to place someone on a Local Station Board.¹² It was a simple matter to stack the new Boards with a dysfunctional crew of yes-men and -women and incompetents, according to DeRienzo. The new members included crack-smoking former DC mayor Marion Barry, while Michael Ratner — Goodman’s lawyer, who had just finished suing Pacifica as legal counsel for the Pacifica Campaign — became the legal counsel for the network itself.

According to a former producer, Goodman around this time threatened to quit Democracy Now and stop raising money unless Pacifica gave her private corporation total ownership of the show and its seven-year archive, free of charge. Having interposed herself between the station’s wealthiest donors and Pacifica, Goodman was responsible for up to 25% of the station’s revenue during fund drives. She struck at a vulnerable time, having (with the help of the Pacifica Campaign) purged at least 56 people for their failure to support her power grab and helped bleed the station dry with petty lawsuits, according to producers. With a green new management board and a depleted war chest weakening any opposition the network could have mounted against her, she set her terms before the new Board Chair, Leslie Cagan. The Board accepted a contract dictated almost exclusively by Ratner, who became sole arbiter; she got all her demands plus $500,000 per year to broadcast Democracy Now on Pacifica stations, plus the $750,000 per year which had formerly accrued to Pacifica through syndication and archival sales. She also gained the rights to solicit donations to her private corporation using Pacifica’s mailing list. Cagan had not consulted with a single one of the 21 other Board members and was being supported financially by Ratner at the time, with a $30,000 payoff “to defray living expenses” as icing on the cake. According to one estimate from a former board member, from 2001 to 2011, Goodman managed to hoover up $77.2 million that would otherwise have gone to Pacifica. She reported Democracy Now’s income in 2011 as $6.5 million, its assets as $13 million, and her own salary as just $148,493.¹³

Perhaps uncomfortable with her audience knowing the truth about the violent and underhanded manner in which she wrested control of Democracy Now from Pacifica’s grasp, Goodman has been reticent in discussing the network’s part in her stratospheric rise.¹⁴ Her Wikipedia entry — now that such bathroom-wall-level scribblings are considered gospel truth — barely mentions Pacifica, and the origins of Democracy Now as a collaborative product are entirely obfuscated. Samori Marksman’s name has been erased from his creation, as has the fact that Goodman was originally meant to be one of five program hosts. The work of Goodman’s supporters in spinning the events of 1999–2002 is all over the internet, papering over what one producer has called a “one-sided ass-kicking” with the Goodman-sanctioned version of events. Those who may consider this current narrative one-sided are reminded that at no time during the Pacifica Campaign’s reign of terror — one veteran producer recalled a participant actually saying “we’re the new Robespierre court” — did they give the other side a fair hearing, instead opting to shoot first and ask questions later.

While Goodman was finalizing what many consider her coup d’état at WBAI, other Pacifica stations were subjected to the same line of personal, professional and legal harassment. Allegedly terrorized on a personal and professional level by the Pacifica Campaign, Pacifica trustees left by the dozen; those who wouldn’t leave were fired, and those who couldn’t be fired were sued. The settlement that “democratized” Pacifica placed the network under an interim Board, most of whom had no experience in radio or even business and reportedly gave away contracts to friends and cronies to predictably chaotic results. This dysfunctional, unelected Board persisted long past the legally mandated period.¹⁵ For over two years, these amateurs ran Pacifica into the ground, which some believe was the intended outcome of the Pacifica Campaign’s legal and personal harassment initiatives, which stripped the network of experience and capital. In May 2003, identity politics became official station policy: a resolution dictating that “priority of programming would be given to groups historically and currently under immediate threat of losing life, liberty and limb, particularly black women” was unanimously passed by the unelected Board, which also voted in a massive increase in Spanish-language programming. While giving a “voice to the voiceless” has always been Pacifica’s stock in trade, the network’s staff were already mostly black even before the settlement, and the resolution carried a whiff of virtue-signaling — an effort to burnish their revolutionary cred with listeners who might have been turned off by the civil war. Just a few weeks after a fund drive, there was a mass purging of KPFK’s best and longest-running programs and directors. Long-time listeners were progressively alienated, according to former Board member Nalini Lasiewicz. “Pacifica began to pride itself on who it did not want listening,” said one producer.

With the National Board firmly in the hands of Goodman’s allies, and Democracy Now safely in Goodman’s possession, the network’s new rulers were free to pursue their pet projects, even if they conflicted with the aims of the stations. With no central administrative control, local boards set their own agendas. Those who had not been purged saw WBAI becoming increasingly politicized, with White rehired along with others Leid had fired. One long-time producer watched in disbelief as the Board rejected a highly-qualified job applicant because “she wasn’t Left enough,” instead picking someone with no experience in radio whose politics were closer to their own. While Pacifica is a nonprofit with an obvious political bent, even nonprofits need to maintain a certain level of funding; the dissenting producer explained that management is normally selected based on professional experience and connections, with an eye toward what they can do for the organization. Picking people based on their revolutionary ideals might have looked good, especially to listeners convinced the old board had to go because it was lousy with bourgeois sellouts, but it sealed Pacifica’s fate financially.

In 2004, White had long-running health and politics show host Gary Null removed from WBAI, even though as much as half the station’s audience was primarily Null’s and he was responsible for the lion’s share of Pacifica’s fundraising. White not only cut Null’s broadcast in the middle of an exposé on the Pacifica coup — he took Null’s broadcasting slot and gave it to his personal physician without informing either Null or his audience. Null, who had two days earlier debated White, Cagan and van Isler for nearly an hour on air, was joined by almost 2,000 of his listeners in protest.¹⁶ The station lost 44,000 listeners — 54% of its audience — and hasn’t made a fundraising goal since. Null began broadcasting on WNYE, only agreeing to return to WBAI when he was told that new management was running the station. Management turnovers are a regular occurrence, according to DeRienzo, because there is no real authority: control of WBAI and the other Pacifica stations is “easy to take over but hard to hold onto.”

Aftermath

In 2005, WBAI signed a prohibitively-expensive 15-year lease renewal on its 50 kW Empire State Building transmitter. The 2005 Board has no memory of seeing or reviewing the lease; DeRienzo posits that even then-Interim Executive Director Ambrose Lane did not read the lease, merely signing it and concealing its existence from the rest of the Board. Lane, a WPFW broadcaster, replaced Dan Coughlin, a Goodman ally, who quit two weeks before the signing. After serving what some believe was his purpose of shepherding through the unaffordable transmitter lease, Lane was replaced by Dan Siegel, who had once sued the network on Goodman’s behalf.¹⁷ When the one-sided Democracy Now contract came up for renewal in 2006, it was once again placed before an inexperienced Board, who were no match for Goodman’s legal sharks. Her lawyers presented the contract as a fait-accompli, convincing the Board to once again sign away their best interests and Pacifica’s only cash cow to the already-wealthy Goodman and her private corporation.

Siegel was elected interim Executive Director over the objections of several Board members, railroaded through by his allies Margy Wilkinson and Lydia Brazon (plus eight others), according to Brown, who has extensively documented what he considers a pattern of sabotage by Siegel. The so-called Save KPFA faction seized power by canceling regularly scheduled elections with an eye toward profiting from Pacifica’s recurring misfortunes — some of which, Brown says, they were responsible for.¹⁸ Siegel and Wilkinson formed a shadow corporation that Siegel admitted was designed to acquire the licenses and assets of Pacifica stations should the network go bankrupt — a bankruptcy that Siegel and Wilkinson were well-placed to engineer in their positions as legal counsel and national Board member. Because they stood to gain from Pacifica’s demise, which could place licenses worth over $100 million in their hands, they were legally obligated to inform the Board of their mammoth conflict of interest — with Siegel doubly obligated due to his additional position as Pacifica’s attorney. But they never informed the Board, and Siegel was later investigated by the California bar for his failure to do so.

Siegel had allegedly been milking Pacifica as legal counsel for years, submitting bills that were not itemized and making decisions despite the conflicts of interest inherent in serving simultaneously as counsel and Executive Director. His instigating role in one of the lawsuits that decentralized control of Pacifica is merely the first conflict of interest in what Brown and others believe to be an extensive career of such conflicts. What some consider Siegel’s thuggish behavior was not limited to the courtroom — in 2007, he allegedly broke into a Pacifica election supervisor’s home, drunk, and harassed his wife.¹⁹ According to Brown, he also sabotaged Pacifica’s defense against a lawsuit brought by a former employee, forcing the network to pay $400,000 to settle a racial discrimination suit that the network should have won. According to Brown and others, Siegel committed this violation of professional ethics as revenge on Pacifica’s Board for forcing him to resign as counsel for reasons of incompetence.²⁰ Other Board members have meticulously documented Siegel’s misdeeds, which appear to be numerous and always leave Pacifica somewhat poorer. Their conclusion, given his ownership of a corporation designed to receive Pacifica’s licenses in the event of bankruptcy, is that Siegel sought to engineer such a bankruptcy, just as Leid and DeRienzo believe Goodman did.

Indeed, some of Pacifica’s behavior is inexplicable unless viewed from the perspective of intentional self-sabotage. Null threatened to quit WBAI again in July 2013, partially out of frustration with how the station managed to alienate listeners, donors and producers all at one go with its mishandling of pledge premiums. He had asked the artist Peter Max, a personal friend, to donate some original and signed prints for a star-studded auction event to benefit Pacifica. Station managers were informed of the plan, and Max contacted celebrity friends who lived in the vicinity of Pacifica stations to encourage them to attend the auctions. Three days before the planned events, Pacifica staff had yet to even speak with Max by phone, let alone confirm any of the logistical details, and the artist had no choice but to cancel his participation. So Pacifica lost the prints, which Max donated to other groups, depriving the network of potential millions of dollars in lost pledge revenue. During another pledge drive, Null offered a two-week health retreat as a premium that earned the station $60,000 in pledge revenue. The station promised to reimburse him for thousands of dollars of expenses afterward but failed to do so until Null threatened to stop fundraising for Pacifica entirely. He is far from the only show host to lose patience over the network’s mishandling of premiums. If the FCC were ever to enforce its own statutes mandating premiums be delivered within 30 days of a pledge, Pacifica could be on the hook for fines running upwards of $130 million.

In 2017, the Empire State Realty Trust began demanding $1.8 million in back rent plus legal fees for WBAI’s 50kW Empire State Building antenna. With monthly rent running over $50,000 — four times the market rate — and increasing at a rate of 9% per year, the cash-strapped station had few options. When an October 2016 judgment found for the Empire State Realty Trust, throwing out an alleged “verbal agreement” reached with the landlord in 2014 in a closed Board session from which Pacifica’s New York real estate attorney was deliberately excluded,²¹ the court opened the door to the landlord seizing Pacifica assets outside New York to pay the debt. With its ultra-valuable FCC licenses now in jeopardy — the same prizes coveted by the competing factions of the network since time immemorial — Pacifica began seriously considering filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, negotiations that dragged on as the landlord filed in California to seize the property of KPFA and KPFK.²² As the vultures circled, the Board secured a $2 million loan assembled by Pacifica members in southern California to pay off the ESRT.²³ By April 2018, Pacifica was able to work out a settlement that relieved the network of its financial responsibilities, liberated WBAI from its ruinously expensive transmitter lease, and allowed the station to take advantage of a standing offer to move to 4 Times Square.²⁴ Warring factions had laid down their swords and united to save Pacifica, if only so they could return to battling for control of its assets.

Some defenders of the status quo protest that Pacifica was mismanaged prior to the 2001 “coup” — even though it had $3 million in the bank, the highest listener numbers in the network’s history, and the most qualified, experienced, and diverse staff reliably producing quality programming. They dismiss those cash reserves, reasoning that they don’t matter because the stations never got to use them, but omitting the fact that the money was frittered away defending Pacifica from lawsuits. They claim Pacifica is better off having purged the formidable progressive General Managers, Program Directors, and Board members whose years of experience in non-commercial radio was an invaluable asset to the network — that their replacement by unqualified rabble-rousers wearing their identity politics on their sleeves is somehow incidental to the network’s decline. Pacifica apologists justify their actions with the argument that there was no real democracy before the restructuring, ignoring how the old bylaws mirrored those of almost every successful non-commercial radio station in the country, prioritizing experience and fundraising ability over radical politics and the willingness to get one’s hands dirty. They ignore the toxic culture of petty internecine squabbles that plays out daily on internet message boards and mailing lists, pretending that the cross-factional cooperation that temporarily saved Pacifica from its creditors was not unusual at all — that it represented the network’s new direction, a new Golden Age that’s always just over the next hill. But in the words of one veteran programmer, “all that anyone at Pacifica has ever done for the last 20 years is double down on stupid.” And the network would not be so lucky the next time.

The Future(?) of Pacifica

Pacifica’s flagship station KPFA has veered far from the progressive path in recent years, canceling Bonnie Faulkner’s beloved program Guns & Butter because of a pair of angry letters written in response to her airing of a provocative presentation by military historian Alan Sabrosky. While the vast majority of KPFA’s audience consists of level-headed adults capable of handling viewpoints different from their own with maturity, these two letter-writers’ opinions apparently overshadowed the history of supporting free speech for which Pacifica is revered. The decision was augured nearly two years before, when KPFA Manager Quincy Jones began using the specter of “fake news” as a lever to pry more money out of listeners during fundraising drives.²⁵ Listener Daniel Borgstrom called this fearmongering out for what it was and many other listeners complained, yet the spot was used for several months, feeding on the McCarthyite climate that has settled over American public discourse in the wake of the 2016 election. How ironic that Pacifica was once the only station brave enough to stand up to Senator McCarthy during the original Red Scare.

Some might say that the corporate raid model, used to such devastating effectiveness by predatory investors in the 1980s, is being used as a model by the Goodman/Siegel crew in their alleged plot to seize Pacifica. By taking control of first the local and then the national Boards, creating an atmosphere of chaos both interpersonal and financial in order to deplete the network’s cash reserves, and swooping in at the last minute via a conveniently-incorporated private company to snatch Pacifica up from bankruptcy, the cabal could be merely following the script that made countless private equity firms rich. We do not expect such behavior from the “progressive” left, and the “real” Pacifica has been victimized repeatedly for assuming its enemies are playing by the same honorable rules. But left-gatekeepers like the heavily foundation-funded Amy Goodman, who has never apologized for her support of US regime change operations in Libya and Syria, where she acted as on-air cheerleader for the terrorist White Helmets, are no more progressive than Hillary Clinton or Barack Obama. Such “limousine liberals” are corporate wolves in progressive sheep’s clothing. Whether or not they are being helped by Deep State interests is immaterial at this point, when the damage has been done, but it’s worth noting that the constant internecine struggles at Pacifica come straight from the COINTELPRO playbook.

Pacifica’s decline is not the fault of Amy Goodman — the network has been rife with dysfunction for as long as anyone I spoke to worked there. Indeed, Goodman, apparently taking pity on the network after nearly two decades of holding the massive Democracy Now debt over its head, reportedly forgave the debt in early 2019²⁶ after repeatedly refusing to do so in the past.²⁷ But the “democratization” of Pacifica’s board by her allies played a large part in its downfall, according to those who witnessed it. Andrew Phillips, who preceded Marksman as Program Director at WBAI and later worked as Interim General Manager at KPFA, explained that democratization “sabotaged” Pacifica: “one would think it would have worked, but it created too much democracy, in a way. Everyone was pulling in different directions.” By enshrining institutional gridlock in Pacifica’s bylaws, the hyper-democratic restructuring — former KPFA General Manager Nicole Sawaya called it “so flat that it is concave”²⁸ — impaired the network’s ability to react and adapt to a changing media climate. Out of touch with the evolving needs of its audience, and no longer the sole progressive voice in the media wilderness, Pacifica has been left behind. Phillips thinks Pacifica could perhaps be saved — if unified, competent management were able to eschew democracy and “nationalize” the network, taking the best programming from each station and putting it “all under one umbrella” anchored by a solid morning show. Until then, WBAI is “an albatross around the neck of the rest of the network,” while the individual stations with their shrinking audiences are “vanity projects” with too few standouts to thrive on their own. Pacifica has value as a stepping stone for people like Goodman, whom Phillips introduced to WBAI in 1984 after she audited his class at Hunter College, but Democracy Now’s budget now reportedly exceeds Pacifica’s.

Because of the one-sided contract between Goodman and Pacifica, the impoverished network now owed Goodman several million dollars for broadcasting Democracy Now, “her” show. In December 2017, Manhattan Neighborhood Network, whose CEO is Goodman crony Dan Coughlin, offered to “save” WBAI by relieving Pacifica of financial responsibility for the station through a Public Service Operating Agreement (PSOA). Such a move would effectively place the station fully within Goodman’s control,²⁹ and the plot was not a new one. As far back as July 2012, Coughlin allegedly submitted a secret bid for a lease management agreement for WBAI’s Empire State Building signal that would have completely absorbed the beleaguered station into MNN.³⁰ Mimi Rosenberg, another long-time Goodman ally from the Pacifica Campaign days, has vocally backed the idea that MNN should take over WBAI, and the Coalition to Save WBAI — an activist faction populated by many of the same faces as the old Pacifica Campaign — drew up a petition in favor of the MNN PSOA, calling the proposed partnership “an exciting solution.”³¹ The proposition was deferred when WBAI received its stay of execution in 2018, but that reprieve was only temporary.

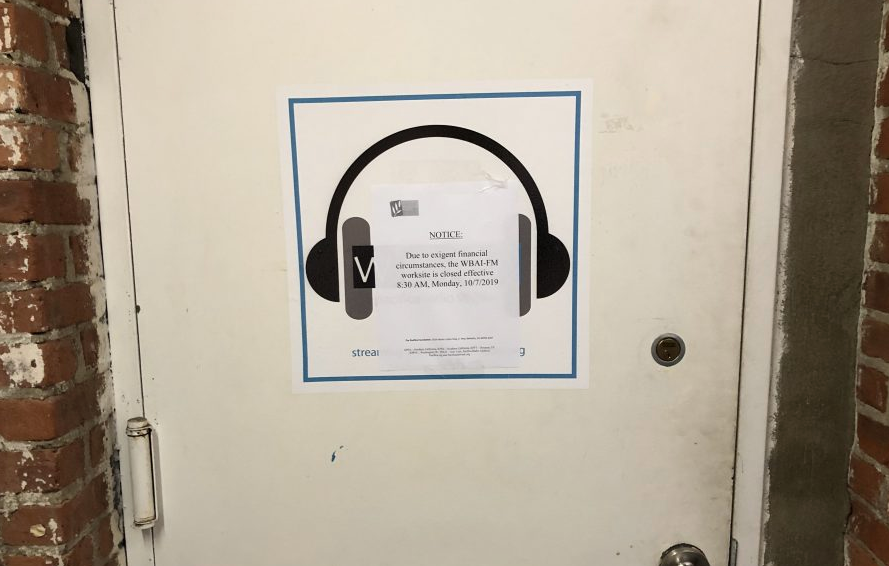

Indeed, the entire network may have climbed out of the frying pan, but it remains engulfed in fire. Several Pacifica board members who opposed the financing deal that saved the network from its debts in 2018 floated a plan to take over the New York station, warning the others that “WBAI is out of control” and would surely bring down the entire network unless its entire staff was replaced.³² Unable to garner sufficient support for a takeover under existing management, Siegel’s Save KPFA faction — now rebranded as the Pacifica Restructuring Project, sans Siegel— attempted to overhaul network bylaws to legitimize the planned coup, but failed. Dissenting board members warned WBAI staff what they suspected was about to go down, but the plot went forward anyway under their noses, cloak-and-dagger style. In October 2019, a handful of board members operating under the direction of Pacifica’s interim Executive Director John Vernile (who’d held his post for all of three months) changed the locks at WBAI’s offices, confiscated their equipment, fired everyone at the station save two, and told the landlady to re-rent the space because they weren’t coming back, all without informing half the board what they were up to. The lockout took place in the middle of a vital WBAI fund drive — as usual, the station was in the red — and programming was replaced with reruns of shows from other Pacifica stations. The sheer cost of the coup — severance pay for ten fired employees, the cancellation of the fund drive, even plane tickets and hotel costs for the board members who comprised the impromptu death squad — would have been prohibitive for cash-strapped Pacifica, unless there was big money at the end of the rainbow — leading many to speculate that the end goal of the takeover was, once again, the sale of WBAI’s license.³³ Certainly the idea of “saving” WBAI was flimsy cover. “If they wanted to save the station, they wouldn’t have gone in there and told the landlady that the station was closed and was not going to open again,” Gary Null, still WBAI’s biggest audience draw, pointed out.

There are other explanations for why the Pacifica plotters went after WBAI when they did. Long-time producer Mimi Rosenberg had recorded a promo that included the phrase “We have to stop Trump” — conflating her personal politics with the station’s, an act that could theoretically endanger its 501(c)3 nonprofit status. Station Manager Berthold Reimers suspended Rosenberg for a week, but refused to force her to pre-tape her shows in the future as Vernile demanded. His loyalty to Rosenberg — who’d been broadcasting for decades — over a corporate exec who’d been running Pacifica for two months reportedly triggered a warning from management that his leadership had imperiled WBAI’s license.³⁴ Was Vernile merely using Rosenberg’s on-air Trump Derangement Syndrome as an excuse? Rosenberg certainly thought so, and said as much on air.³⁵ WBAI listener-delegate and temporary chair of the Pacifica board Alex Steinberg suggested the coup was “a ‘cleansing’ operation to remove any dissident voices to the left of the Democratic Party establishment from having any say on the politics and culture of this country,” hinting that there was “big money” behind Vernile³⁶ (and KPFA Station Manager Quinn McCoy, suspected by some of having engineered the hire of Vernile specifically to take out WBAI³⁷).

Regardless of why it happened when it did — almost exactly 20 years after a similar lockout-coup at KPFA — the takeover was total, including even WBAI’s bank accounts, indicating the presence of a traitor in the station’s ranks who gave up the station’s passwords, likely in return for being spared the axe. More importantly, the coup was flagrantly illegal, and a New York judge demanded a reversal of the entire mess. That decision took time to enforce, however, and after five weeks offline, the damage was done. The station’s audience — what little remained of it — was gone. The coup had technically failed; Vernile was put on paid leave, while the vice-chair and secretary of the Pacifica board, both of whom had backed the takeover, were removed.³⁸ But over a month offline had succeeded in killing the station, or at least mortally wounding it: Null gives WBAI six months to live.

This is how a one-of-a-kind network with a 60-year history in some of the most progressive cities in the US and prime dial space is millions of dollars in the hole, on the brink of bankruptcy, its staff in perpetual turmoil, unaware who even owns the loan that could be called in at any moment to snuff out the network.³⁹ Thwarted once from seizing hold of all of Pacifica, Amy Goodman and the faction that surrounds her never gave up — whatever criticism former colleagues may have of her, none can say she is not shrewd, driven, and fiercely dedicated to her goals. Goodman now has the legitimacy her former colleagues say she has always craved since she was reportedly fired from NPR — indeed, she has long since outgrown Pacifica, emerged from its rapidly-desiccating husk like a COINTELPRO butterfly to become a leading figure in the who’s-who of Corporate Progressivism™. History is written by the victors, and the story of Pacifica has been reported almost exclusively by voices loyal to Goodman and the Pacifica Campaign; all we are trying to do is bring balance to the narrative by telling the stories of those who were so effectively vilified and chased out of the network — to bring a voice to the voiceless, as Pacifica itself might have put it in better days. This is the story of the downfall of a once-formidable broadcast network — a decline that began long before Goodman arrived on the scene and which will continue until the network is either put out of its misery or, by some miracle, saved.

NOTES

This report was compiled primarily from interviews with current and former Pacifica staff. They are either named in the text or wished to remain anonymous out of concern about retaliation. Requests for comment sent to Amy Goodman, Juan Gonzalez, and Bernard White were ignored. Dan Coughlin agreed to be interviewed, but was not present for most of the events depicted in this report; he denies any “secret contract” or “secret lease renewal” or “secret bid” and insists Goodman was lovely to work with. To anyone who might complain that I “only” attack the Left, I will say that it is because of the sheer incompetence of what passes for the “Left” in the 21st century that the country is where it is today. This appalling culture of appeasement, navel-gazing, and infighting has given us a “Left” that cheers on the CIA and FBI, embraces endless war, and shuts down any discussion of controversial subjects with an authoritarian response that would make any right-wing fascist proud. We expect this from the Right — but the “Left” of 2019 has abandoned the working class to serve the same interests it was convinced were going to steal Pacifica. Congratulations, you’ve become the enemy.

1 Gonzalez, Juan. “Juan Gonzalez Resignation Letter.” Free Pacifica Radio! 31 Jan 2001. http://freepacifica.savegrassrootsradio.org/freepacifica/013101juan_resigns.html

2 Cockburn, Alexander and Jeffrey St. Clair. “Explosive Pacifica Radio Memo Raises Storm.” Counterpunch. 13 Jul 1999. https://web.archive.org/web/20010208213808/http://www.counterpunch.org/sellmemo.html

3 Spooner, Carol. “Updates on Lawsuits Challenging Hostile Takeover By Pacifica Board of Directors.” Free Pacifica Radio! 1 Mar 2001. http://freepacifica.savegrassrootsradio.org/freepacifica/legal.htm

4 DeRienzo, Paul. “Steve Yasko and the Adventures of Mike Bilt.” NWO.MEDIA. http://nwo.media.xs2.net/articles/message/message2d.html Accessed 4 Oct 2018.

5 Cooper, Marc. “Public Statement on Pacifica.” The Nation. 4 Oct 2001. https://www.thenation.com/article/public-statement-pacifica/

6 Hentoff, Nat. “Can WBAI Be Saved?” Village Voice. 10 Apr 2001. https://www.villagevoice.com/2001/04/10/can-wbai-be-saved/

7 Milano, Scott. “Freedom of Speech.” Builder Magazine. 14 Dec 2001. https://www.builderonline.com/money/freedom-of-speech_o

8 Hinckley, David. “Dissidents Confident They’ll Win WBAI Fight.” NY Daily News. 1 Aug 2001. http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/entertainment/dissidents-confident-win-wbai-fight-article-1.930828

9 Gerry, Lyn. “[EMMAS] Direct Actions Against Ken Ford & NAHB.” misc.activism.progressive (newsgroup). 1 Jul 2001. https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/misc.activism.progressive/FvsL3S4INDM

10 Allen-Agostini, Lisa. “Wash Leaves Top Post at Embattled Pacifica.” Washington Post. 2 Nov 2001. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/2001/11/02/wash-leaves-top-post-at-embattled-pacifica/8a1867ad-4a4d-4665-a159-dff03538cae8/?utm_term=.c8c0e487ae75

11 Pacifica Campaign. “Pacifica Radio’s Utrice Leid Resigns.” Autonomedia. 12 Dec 2001. http://dev.autonomedia.org/node/594

12 Guma, Greg. “Pacifica Radio’s Progressive Meltdown Continues.” Maverick Media. 22 Mar 2014. http://muckraker-gg.blogspot.com/2010/08/pacifica-radios-progressive-plight.html

13 Brown, Steven M. “How Much Does Pacifica Owe to Amy Goodman & Democracy Now?” Educate Yourself. 28 Mar 2014. http://educate-yourself.org/cn/How-Much-Money-Does-Pacifica-Owe-to-Amy-Goodman-and-Democracy-Now28mar14.shtml

14 KPFKCommentator. “Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now! — on KPFK too.” KPFK.***.Commentators.HERE. 30 May 2017. http://kpfkcommentators.blogspot.com/2017/05/amy-goodmans-democracy-now-on-kpfk-too.html

15 Gonzalez, Juan. “Pacifica Campaign Announces Legal Settlement.” Autonomedia. 13 Dec 2001. http://dev.autonomedia.org/node/595

16 moot point. “The Great Turning of WBAI from Progressive Radio to a Black Nationalist community station.” WBAI Issues Forum (Archive 1). 30 May 2006. http://www.listenerforums.net/cgi-bin/archivei_config_a1.pl?md=read;id=52370

17 Rosenberg, Tracy. “What the Dickens is Going On?” Pacifica in Exile. 28 Dec 2017. http://pacificainexile.org/archives/2518

18 Borgstrom, Daniel. “DAN SIEGEL and the KPFA/Pacifica Election of 2007.” Daniel’s Free Speech Zone (blog). 1 Feb 2009. http://danielborgstrom.blogspot.com/2009/02/dan-siegel-at-pacifica-radio.html

19 Peters, Casey. “Final Report on the Pacifica 2007 Elections.” Pacifica Elections Report. http://www.pacificaelections.net/2007-8%20pacifica%20elections%20final%20report.pdf Accessed 4 Oct 2018.

20 Rosenberg, Tracy. “Time to Stop Dan Siegel.” Pacifica in Exile. 21 Jan 2016. http://pacificainexile.org/archives/1636

21 Albertson, Chris. “Exiles’ gloomy return.” WBAI: Pacifist Battleground. 28 Dec 2017. http://wbai-nowthen.blogspot.com/2017/12/exiles-gloomy-return.html

22 Albertson, Chris. “Breaking the silence…” WBAI: Pacifist Battleground. 27 Dec 2017. http://wbai-nowthen.blogspot.com/2017/12/breaking-silence.html

23 Rosenberg, Tracy. “The End Less Near — Pacifica Board Approves Loan.” Pacifica in Exile. 19 Jan 2018. http://pacificainexile.org/archives/2552

24 Livingston, Tom. “Pacifica Announces Settlement With Empire State and Empire State Realty Trust.” WBAI. 6 Apr 2018. https://www.wbai.org/articles.php?article=3570

25 Borgstrom, Daniel. “Whatever Happened to the First Amendment? KPFA’s ‘Fake-News’ Pitch and the Ministry of Truth.” CounterPunch. 30 Dec 2016. https://www.counterpunch.org/2016/12/30/whatever-happened-to-the-first-amendment-kpfas-fake-news-pitch-and-the-ministry-of-truth/

26 Lasar, Matthew. “Riding the waves at Pacifica radio, by Andrew Leslie Phillips.” Radio Survivor. 6 Aug 2013. http://www.radiosurvivor.com/2013/08/06/riding-the-waves-at-pacifica-radio-by-andrew-leslie-phillips/

27 Mills, Ken. “The True Story of How Amy Goodman Became the Owner of ‘Democracy Now!’” Spark News. 16 Feb 2018. http://acrnewsfeed.blogspot.com/2018/02/the-true-story-of-how-amy-goodman.html

28 Stop the Power Grab. “Shock Doctrine: Power Grab At Pacifica To Destroy WBAI By KPFA Cabal.” IndyBay. 12 Sep 2019. https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/09/12/18826188.php

29 Sisario, Ben. “Democracy May Prove the Doom of WBAI.” New York Times. 21 Aug 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/21/business/media/democracy-may-prove-the-doom-of-wbai.html

30 Rosenberg, Tracy. “A Timeline of the Coup.” Pacifica in Exile. 30 March 2016. https://pacificainexile.org/archives/1817

31 Riley, John. “The Financial Decline of WBAI & Pacifica and an Exciting Solution.” Save WBAI. 16 Feb 2018. http://savewbai.org/2018/02/16/the-financial-decline-of-wbai-pacifica-and-an-exciting-solution/

32 Handala, Jara. “‘The goal of these behind the scene machinations is not the revival of WBAI but its dismantling’ — Pacifica directors sound the alarm.” PacificaWatch. 13 Sep 2019. https://pacificaradiowatch.home.blog/2019/09/13/the-goal-of-these-behind-the-scene-machinations-is-not-the-revival-of-wbai-but-its-dismantling-pacifica-directors-sound-the-alarm/

33 Pacifica Radio in Exile. “Supreme Court of New York Stops Pacifica’s Attack on WBAI.” Popular Resistance. 8 Oct 2019. https://popularresistance.org/supreme-court-of-new-york-stops-pacificas-attack-on-wbai/

34 Schwartz, Arthur. “WBAI Signs Off. Its Future Remains Uncertain.” The Nation. 11 Oct 2019. https://www.thenation.com/article/radio-pacifica-wbai/

35 McGoldrick, Meaghan. “‘We need WBAI’: Station’s supporters vow to keep fighting for local programming.” Brooklyn Eagle. 15 Oct 2019. https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2019/10/15/wbai-supporters-vow-to-keep-fighting-for-local-programming/

36 Steinberg, Alex. “My guess is that there is big money and powerful people behind Vernile and Quincy McCoy.” PacificaWatch. 19 Oct 2019. https://pacificaradiowatch.home.blog/2019/10/19/qt-my-guess-is-that-there-is-big-money-and-powerful-people-behind-vernile-and-quincy-mccoy-qt-temp-pacifica-chair-alex-steinberg/

37 “IEW Vernile already came into the job with ‘Pacifica Across America’: Quincy McCoy at the Sa17Aug2019 KPFA LSB.” PacificaWatch. 17 Oct 2019. https://pacificaradiowatch.home.blog/2019/10/17/iew-vernile-already-came-into-the-job-with-pacifica-across-america-quincy-mccoy-at-the-sa17aug2019-kpfa-lsb/

38 Rosenberg, Tracy. “NY Judge Undoes Coup.” Pacifica in Exile. 8 Nov 2019. https://pacificainexile.org/archives/2833

39 “Has FJC sold the $3.265m loan? Is the owner the Marty & Dorothy Silverman Foundation — or have they in turn sold it on?” PacificaWatch. 20 July 2019. https://pacificaradiowatch.home.blog/2019/07/20/has-fjc-sold-the-3-265m-loan-is-the-owner-the-marty-and-dorothy-silverman-foundation/